Vienna Chamber Orchestra & Westminster Choir performing Beethoven's Ninth © TPT

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony is one of the most enduring and revered musical works of all time. Politically, the period in which Beethoven was writing saw the French revolution, Napoleonic expansion and the Restoration. Socially, the bourgeoisie grew in importance and, spiritually, the substantial growth of German philosophy and literature and the initial and most original aspects of romanticism were a major influence.

Beethoven was a deep thinker who was concerned with social problems and new ideas; the French Revolution left a strong and powerful mark on his thinking. He followed political events closely in the newspapers and experienced war first hand when Napoleon's troops invaded Vienna in 1805 and 1809. For him, music did not just exist per se, but was pregnant with meaning and almost always embodied an idea. Throughout his life, and even in its happier periods, Beethoven was beset by the torments of his deafness, financial straits and unhappiness in love. The Kantian ideals of the Enlightenment culture of the time provided a focus for Beethoven’s knowledge and internal life.

For his Ninth and final symphony, the German composer wove the themes of the Enlightenment into his work. He finally saw a chance to use Friedrich Schiller's “Ode to Joy”. Beethoven had long wanted to set the poem to music for its themes of freedom and brotherhood. Written in 1785 — on the brink of the French Revolution — the popular poem expressed a yearning for peace and egalitarianism: “All men shall become brothers… Be embraced, you millions!” The composer’s decision to bring a choir into the piece was revolutionary, giving soaring voice to the poem.

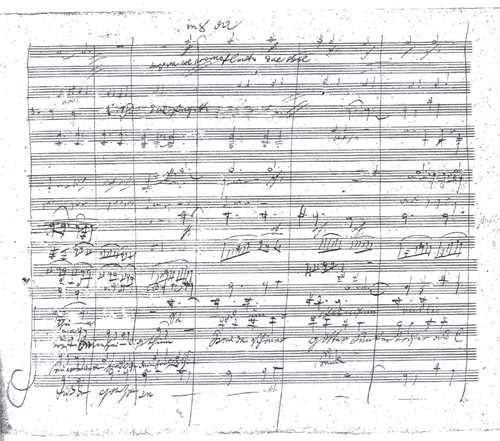

Handwritten page of Beethoven Ninth Symphony

In May 1824, the Ninth Symphony received a standing ovation at its premiere in Vienna. It was the first time Beethoven had appeared on stage in 12 years. Owing to his hearing loss, the story goes that one of the soloists had to stop him conducting after the music had ended and turned him around to accept his applause. The audience, well aware of Beethoven’s health and hearing loss, in addition to clapping, threw their hats and scarves in the air so that he could see their overwhelming approval.

On a purely musical level, perhaps no other piece of music has exerted such an impact on later composers. How, many wondered, should one write a symphony after the Ninth? Schubert, Berlioz, Brahms, Wagner, Bruckner, Mahler — the list goes on — all dealt with this question in fascinating ways that fundamentally affected the course of 19th-century music. Schubert, who apparently attended the premiere, briefly quoted the 'joy' theme in his own final symphony, written the following year. Almost every Bruckner symphony begins in the manner of the Ninth — low string rumblings that seem to suggest the creation of a musical world. Mendelssohn, Mahler and Shostakovich followed the model of a choral finale. Wagner was perhaps the composer most influenced by the Ninth, arguing that in it, Beethoven pointed the way to the “Music of the Future”, a universal drama uniting words and tones — in short, Wagner’s own operas.

But composers were not the only ones to become deeply engaged with the Ninth, to struggle with its import and meaning. In the 20th century, the “Ode to Joy” has been a truly multipurpose composition, claimed by disparate groups. Hitler had it played on birthdays and included it in Nazi propaganda films. Japan’s imperial government used it to raise morale during the second world war. The unrecognized state of Rhodesia, one of white minority rule, adopted it as its national anthem in the mid-1970s.

The Ode has also been a hymn to freedom and has given heart to protesters. Chilean demonstrators sang it under Pinochet and students broadcast it at Tiananmen Square. Many will remember a remarkable world-wide broadcast of Leonard Bernstein performing the Ninth in Berlin on Christmas Day 1989, soon after the city's reuniting. Leading an international orchestra and chorus made up of musicians from east and west, Bernstein changed Schiller's text from an “Ode to Joy” (An die Freude) to an “Ode to Freedom” (An die Freiheit).

Bernstein during the East-West Concert in Berlin, Dec 25, 1989 © dpa

Since its premiere, performances of the Ninth Symphony have become almost sacramental occasions, as musicians and audiences alike are exhorted to universal fraternity. The Ninth has been used at various openings of the Olympic Games, bringing all nations together in song. In 1972, a standing committee on the Council of Europe declared that the Ninth “was representative of European genius and was capable of uniting the hearts and minds of all Europeans”. The “Ode to Joy” was adpoted as the European anthem — not intended to replace national anthems but rather to celebrate the values they share. In 1985 it became the official anthem of the European Community, then the European Union, from 1993.

Join a group of classical music lovers in Austria and enjoy Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony performed by the Vienna Philharmonic under the baton of Andris Nelsons on Special Travel International’s Classical Austria tour (May 26 – June 9, 2020).

On the Horizon for 2024-25

Travel the world with like-minded people, and discover how much shared enthusiasm increases your enjoyment of experiences tailored to your interests. All while you enjoy all the comfort and reassurance of traveling in a group. We believe in making extraordinary memories with friends, exceptional service and ethical business conducted with proven local partners.

Special Travel crafts unique tours for choirs, sport teams and many other special interest groups.

Contact Email

CLASSICAL MUSIC PLATFORM

Find out more about our artists and Classical Music partners

Click Here